Stock Pickers

Stock PickersAs we learned in Step One, courtesy of The Wolf of Wall Street, no one can predict with certainty the direction of a stock. Think about it from a purely logical perspective: is it realistic to presume that an individual investor or a stock broker can know more than the combined knowledge of ten million traders? I estimate that approximately five million sellers and five million buyers place trades each day. With each trade, a buyer and a seller both agree upon a price which represents the best estimate of a fair price.

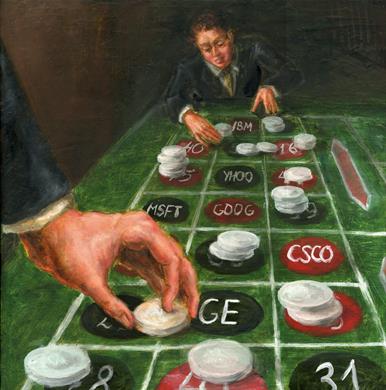

Rex Sinquefield describes the market as a vast processing machine that compiles all knowable information, much like a “collective brain.” This concept is represented in the painting to the right and articulated by Sinquefield back in 1995, at a debate on active vs. passive investing, Sinquefield put it this way: “So you can have one individual who can be very, very smart and actually know a little bit more than everyone else. But does he know more than six billion people combined? No. He knows a tiny, tiny fraction of what is knowable and what is built into prices. That’s sort of the intuition why no one’s ever going to get an edge over the market.”1

Stock prices are quickly moved by news that is available to virtually all market participants at the same time. Because news is unpredictable and random by nature, we come to the unavoidable conclusion that movements of stock prices are also unpredictable and random. Therefore, the current stock price is the best estimate of the stock’s fair price. This means those celebrity stock pickers appearing on television and the silver screen are no different than a team captain calling a coin toss before a big game. It’s a blind guess as to whether the stock will go up or down in the short term because these events will occur based on news that is unknowable in advance. This means your portfolio, if based on a few hand-picked stocks, will rise or fall on the whims of the daily news.

Ever since the first stock market trade, which took place in 1602 at the Amsterdam Stock Exchange (“Vereniging voor de Effectenhandel”), traders have been looking for ways to predict future stock market movements. They have studied reams of data in search of patterns in securities prices. In 2000, a Nova television special, “The Trillion Dollar Bet,”2 reported that a group of academics in the 1930s decided to find out if traders really could predict how prices moved. Since they could not find any scientific basis for the belief, they decided to run a series of experiments. In one of them, they created a random portfolio of stocks by throwing darts at The Wall Street Journal while blindfolded. After one year, they were stunned to discover the dartboard portfolio had outperformed the portfolios of Wall Street gurus. The academics arrived at a devastating conclusion: The success of top traders was simply due to luck, and patterns in prices appeared by chance alone.

In 1992, 63 years after the stock market crash, John Stossel of ABC’s 20/203 program conducted some follow-up research on the dart throwing. He determined the economists’ findings from more than six decades prior remained true. Stossel interviewed Princeton Professor Burton Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street. Professor Malkiel reminded viewers that stock markets have historically delivered a performance of 9.5% to 10% per year. “To beat the average, should an investor listen to the Wall Street professionals?” Stossel asked. “No,” replied Malkiel. “All the information an analyst can learn about a company, from balance sheets to marketing material, is already built into the stock price because all of the other thousands of analysts have the same information. What they don’t have is the knowledge that will move the stock such as news events, which are unpredictable and impossible to forecast.”

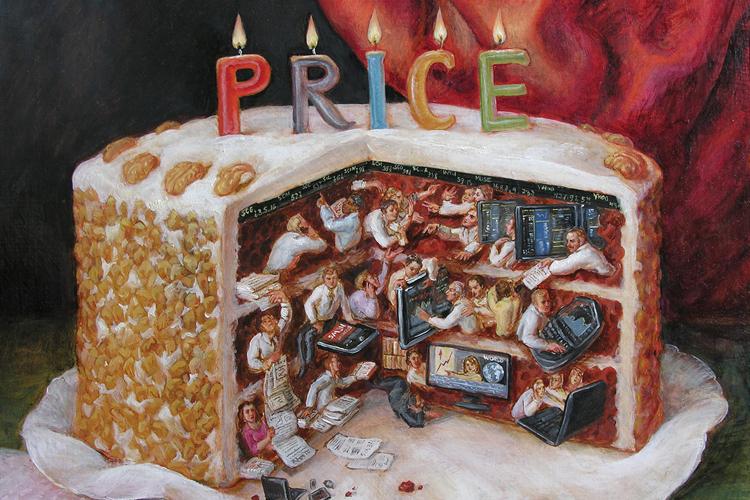

Stock pickers don’t realize that virtually all of the information and forecasts about a stock, a sector, or an economy is quickly digested by the totality of market participants and swiftly embedded into the price. This market efficiency ensures that prices agreed upon between willing buyers and willing sellers are the best estimate of fair market values. As illustrated in the previous painting, available information and news is “baked in the cake,” and no one has special knowledge that is not already included in the price, except for inside information (which is illegal). No single trader can know more or have a consistent advantage over the millions of other market participants around the world. Markets reward investors, not speculators.

Baked in the Cake

Baked in the CakeTenets of market efficiency do not state that prices are perfect or that at any given time there are no mispriced securities in the marketplace. Rather, these tenets assert that because prices reflect all known information, mispriced securities cannot be identified in advance.

Stock pickers are inherently biased about their abilities to pick winning stocks. In a study titled, “Are Investors Reluctant to Realize Their Losses?,”4 Terrance Odean, professor of finance at the University of California, Berkeley, analyzed the activity of 10,000 discount brokerage accounts. Odean’s findings, published in the Journal of Finance, showed that investors habitually overestimated the profit potential of their stock trades. In fact, they would often engage in costly trading, even though their profits did not cover even their transaction costs. Odean’s research showed investors believed they had unique information which would give them an edge, when in reality the information was widely known. On average, the stocks investors bought underperformed the stocks they sold.

In a follow-up paper, “Trading is Hazardous to Your Wealth: The Common Investment Performance of Individual Investors,”5 Odean joined Brad Barber of University of California, Davis to analyze 66,465 individual trading accounts from 1991to 1996. They found that investors who traded most earned annualized returns of 11.4%, while in the same period the market earned annualized returns of 17.9%. Excessive trading resulted in inferior returns compared to the market.

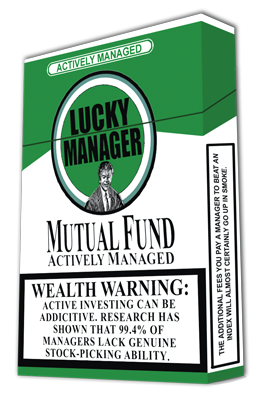

The media loves a good story. Can you blame them? So when a stock picker finds random success, the media adorns them with guru status. When their fleeting success fades, the guru title is handed to the next lucky stock picker. Unfortunately, luck is not a repeatable skill. Mark Hulbert clearly articulates this fact in his 2008 New York Times article, “The Prescient are Few.”6 The article details the findings of a study7 by professors Laurent Barras, Olivier Scaillet and Russell Wermers about the performance of 2,076 mutual fund managers over the 32-years from 1975 to 2006. The study found that 99.4% of the managers displayed no evidence of genuine stock picking skill, and that the 0.6% of managers who did outperform the index were “statistically indistinguishable from zero,” or as Hulbert puts it, “just lucky.” Figure 3-1 depicts the study’s results.

Figure 3-1(permalink)

A statistical test called the Student’s t-test was introduced in 1908 by William Sealy Gosset, referred to as the “Student,” while working for the Guinness brewery in Dublin, Ireland to evaluate the quality of the brewery’s ingredients. The t-test can be used to determine if a series of historical returns is reliably superior – showing a t-statistic of 2 or higher – to a risk-equivalent benchmark. This can determine whether alpha (returns relative to its benchmark return) is due to luck or skill. In Figure 3-2, the t-test is applied to U.S. equity funds in six different style classifications over a 20-year period. Out of 438 mutual funds constructed with at least 90% U.S. equities, 98.4% of those fund managers did not have a statistically significant alpha, meaning any alpha they did have was due to luck, not skill. See the Step 5 Solutions section for a further explanation of the t-statistic.

Figure 3-2(permalink)

Needle in a Haystack

Needle in a HaystackVanguard Group founder John Bogle has accurately described the practice of stock picking as "looking for a needle in a haystack." Even if you are lucky enough to pick a stock that outperforms the market, there is no certainty of success, or even survival, in the future.

In their book, Creative Destruction,8 McKinsey & Company consultants Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan analyzed the companies of the original S&P 500 Index from 1957. Their findings shown in Figure 3-3 revealed that only 74 companies remained on the list in 1997, and just 12 of them ended up with returns that outperformed the index for the 41-year period through 1998. "As the '80s passed and we made our way through the '90s, both of us observed that almost as soon as any company had been praised in the popular management literature as excellent or somehow super durable, it began to deteriorate," the authors wrote. "Searching for excellent companies was like trying to catch light beams; they were easy to imagine, but so hard to grasp," they concluded.

Figure 3-3(permalink)

Figure 3-4 lists the ten largest bankruptcies from January 1981 through December 2013, reminding stock pickers of big companies gone bust. Lehman Brothers, Washington Mutual, GM, and MF Global Holdings were among the big companies that ultimately failed, and the number of bankruptcies significantly increased from 19,695 in 2006 to 47,806 in 2011, and stayed relatively high even in 2013 with 33,212 business bankruptcies.

Figure 3-4(permalink)

Remember Peter Lynch’s advice about buying companies whose products you like? It turns out this advice is not as good as it sounds. Great companies don’t make great investments. You may love Elon Musk, but this doesn’t mean Tesla is a great stock to buy. In fact, the opposite is usually true. Distressed companies have earned higher returns than those of companies with lots of hype or goodwill at the time of purchase. Unfortunately, investors generally avoid investing in distressed companies, because it seems counterintuitive to buy perceived losers.

Finance Professors Meir Statman and Deniz Anginer wrote a 2010 study called “Stocks of Admired Companies and Spurned Ones.”9 Their study was based on Fortune Magazine’s annual list of “America’s Most Admired Companies” from 1983 to 2007. Fortune’s annual surveys ranked companies on eight attributes of reputation:

- Quality of management

- Quality of products or services

- Innovativeness

- Long-term investment value

- Financial soundness

- Ability to attract, develop and keep talented people

- Responsibility to the community and the environment

- Wise use of company assets

From these ratings, Statman and Anginer constructed two portfolios, each consisting of one half of the Fortune stocks. The “admired” portfolio (often referred to as growth stocks) contained the stocks with the highest Fortune ratings, and the “spurned” portfolio (often referred to as value stocks) contained the stocks with the lowest Fortune ratings. For example, the list of admired companies included The Walt Disney Company, UPS and Google. Spurned companies included Jet Blue, Bridgestone and Stanley Works.

The results of the study are no surprise to value investors. “Stocks of admired companies had lower returns, on average, than stocks of spurned companies.” Figure 3-5 shows the 16.12% annualized return of the spurned portfolio and the 13.81% annualized return of the admired portfolio over the 24-year, nine-month period.

Figure 3-5(permalink)

Why have value stocks delivered higher returns to their investors? The market perceives value companies to be riskier, driving down stock prices so their expected returns are high enough to attract investors. That is difficult for most investors to grasp since they prefer to believe growth stocks are better investments than value stocks. After all, investors looking for a stock tip want to hear the name of the next Apple, not the next JCPenney. As you will see in Step 8, the data indicates that investors should be interested in great investments (value stocks), not just great companies (growth stocks).

I analyzed Fortune’s “Ten Most Admired Companies” (2001)10 as a whole portfolio and as individual companies, comparing them to 10 index portfolios for the 17-year period from January 2001 through December 2017. The results of the study are shown in Figure 3-6, indicating the equal-weighted (across the nine remaining publicly traded companies) “Fortune Most Admired Portfolio” underperformed many of the index portfolios — getting about the same returns as Index Portfolio 75 which has 25% fixed income. Despite the fact that the “Fortune Most Admired Portfolio” carried comparable risk to the riskiest Index Portfolio 100, $100,000 grew to $336,000 for the time period vs. $409,543 for Index Portfolio 100. The story is even worse for the “Fortune” tellers. Four of the ten companies took on significantly greater risk than the Index Portfolio 100, but earned returns lower than the Index Portfolio 40 which contains 60% fixed income. Important to note, one of the “Ten Most Admired Companies,” Dell Computer, ceased to exist as a public company and reverted to a private company in 2013.

Figure 3-6(permalink)

This sort of data begs the question: If stock picking is such a fruitless endeavor, why do magazines keep selling this elusive dream? The answer is quite simple: Pro-index fund stories don’t sell magazines. No big brokerage house would take out a full-page ad that says, “Don’t hire us to trade your portfolio — just index and relax.” Nonetheless, this is a poor reason to perpetuate the myth that financial journalists or “Fortune Tellers” can pick the handful of stocks to achieve wealth. In fact, by the looks of it, the best way to lose a fortune is to follow Fortune.

A name that has been synonymous with active bond management is Bill Gross, formerly of PIMCO. Gross is known for his 27 year reign (26 full calendar years) at the helm of the PIMCO Total Return fund (PTTRX). There is no denying that his overall record is impressive, with only seven years in which the return fell short of the Morningstar analyst assigned benchmark. However, as Mr. Gross implied in his April 2013 Investment Outlook letter, luck played a substantial role in that leverage was used during a time period when it yielded a handsome payoff.

“All of us, even the old guys like Buffett, Soros, Fuss, yeah—me too, have cut our teeth during perhaps a most advantageous period of time, the most attractive epoch, that an investor could experience… An investor that took marginal risk, levered it wisely and was conveniently sheltered from periodic bouts of deleveraging or asset withdrawals could, and in some cases, was rewarded with the crown of ‘greatness.’ Perhaps, however, it was the epoch that made the man as opposed to the man that made the epoch” Gross opined.11

Gross’s fund was the largest fixed income mutual fund in existence with more than $230 billion of assets. And, then came 2013-2014. Gross’ fund hemorrhaged assets, losing more than $68 billion during 16 straight months of negative flows as it trailed Barclays Aggregate Bond Index benchmark by 1.45 percentage points.12 Morningstar downgraded PIMCO’s overall stewardship grade from a B to a C as a most public falling out ensued between Bill Gross and his former Co-Chief Investment Officer Mohamed El-Erian. Amidst reports of bizarre behavior, Gross unceremoniously departed PIMCO in September 2014. In the wake of the news, another $27 billion exited the fund within five days of Gross’ departure, leaving investors concerned about the future of their investment in the fund.

Interestingly enough, during his tenure as an active fund manager at PIMCO, Mr. Gross joined the ranks of Warren Buffett and Peter Lynch in giving a solid endorsement to indexing. In his December 2013 Investment Outlook letter, Gross reminisced about his younger days when Jack Bogle introduced the first index fund available to retail investors:

“His [Bogle’s] early business model at Vanguard promoting index funds was a mystery to me for at least a few of my beginning years at PIMCO. Why would most investors be content with just average performance, I wondered? The answer is certainly now obvious; an investor should want the highest performance for the least amount of risk, and for almost all measurable asset classes, index funds and many ETFs have done a better job than almost all active managers primarily because of lower fees.”13

Rather than spending time and resources searching for the stock or bond that will outperform in the future, all investors are better served by indexing in all asset classes.

The Collective Brain

The Collective BrainIt may be easy to understand the allure of stock picking, but looking for a needle in a haystack is not the answer. This pursuit may be very lucrative for stock brokers. “After all, it’s exciting, fun to dip and dart, pick stocks and time markets; to get paid high fees for this, and to do it all with someone else’s money,” quips Rex Sinquefield.14 Unfortunately, however, this well-worn pursuit has proven to be far less rewarding for their clients.

Picking stocks or bonds is an ill-fated strategy that wastes time, energy and money. The better solution is to trust the collective brain, buy the haystack, and maintain risk-appropriate exposures in low-cost globally diversified index portfolios.